A more important question is does hip bursitis exist? Historically, the term "trochanteric bursitis" was used to describe any pain around the outside or lateral hip. However, advanced imaging and histopathologic studies have shown that involvement of the trochanteric bursae in patients with lateral hip pain is uncommon.

Thus, trochanteric bursitis is a misnomer when it used to describe lateral hip pain and when present is usually associated with a gluteal tendon tear/tendinopathy, hip joint pathology or hip instability (Woodley et al. 2008).

Lateral hip pain is now often referred to as greater trochanteric pain syndrome, and in most cases of lateral hip pain there is evidence of tendon degeneration on imaging (Woodley et al. 2008). In one retrospective study, 36% of patients with lateral hip pain still had pain at 1-year and 29% still had pain after 5-years (Lievensen et al, 2005). This suggests that in chronic cases the pain over the side of the hip may not resolve without intervention.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is relatively common in both physically active and sedentary patients affecting 15.0% in women and 8.5% in men (Segal et all, 2007). Risk factors for GTPS include female gender, obesity, knee pain, and low back pain (Fearon et al, 2013). Other conditions associated with lateral hip pain include articular conditions of the hip, knee, and foot; and painful foot disorders such as plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, bunions, Morton neuroma, or calluses.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is due to repetitive overloading of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles and tendon, and pain is due to mechanically failure of the tendons.

In most cases, greater trochanteric pain syndrome is thought to be due to repetitive microtrauma rather than an inflammatory bursal condition alone (Reid, 2016). Cortisone injections (corticosteroids or steroid injections) are anti-inflammatory medications that reduce inflammation, which causes pain and swelling. Cortisone injections can be effective in the short term, but if the hip pain is due to tendon degeneration injections then minimizing inflammation with a cortisone injection is unlikely to address the underlying problem (Khan et al, 2000).

In fact, limited evidence supports the long-term benefit of cortisone injections for the management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, cortisone injections had no benefit over a saline placebo injection at either the 3-months or 6-months follow-up after the injection (Nissen et al, 2019).

Multiple percutaneous techniques have been described for greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Treatments that have been shown to be helpful include percutaneous tendon fenestration, platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections or percutaneous ultrasound-guided tenotomy with Tenex.

In two recent systematic reviews of gluteal tendon treatments, the authors found good evidence for the use of platelet-rich plasma injections (Ladurner et al. 2021; Ali et al. 2018). Significant improvement was noted when patients were followed up at 3-months and 12-months after the injection, and one review found that “PRP seems a viable alternative injectable option for [greater trochanteric pain syndrome] refractory to conservative measures.”

In a study that provided long-term data. patients were followed for 2-years after the PRP injection (Fitzpatrick et al. 2019).

The authors found that a single ultrasound-guided leucocyte-rich

platelet-rich plasma (PRP) treatment for gluteus and medius tendinopathy

resulted in a greater improvement in pain and function compared with a

single corticosteroid injection.

In another study by Jacobson et al. the authors compared PRP to a percutaneous tendon fenestration with a needle (a different procedure than a tenotomy with Tenex) (Jacobson et al. 2016). The study was small and had short follow-up only averaging only 92 days, and patients in the PRP group reported a greater improvement (71%) compared to the needle fenestration group (79%) although this difference didn’t reach statistical significance.

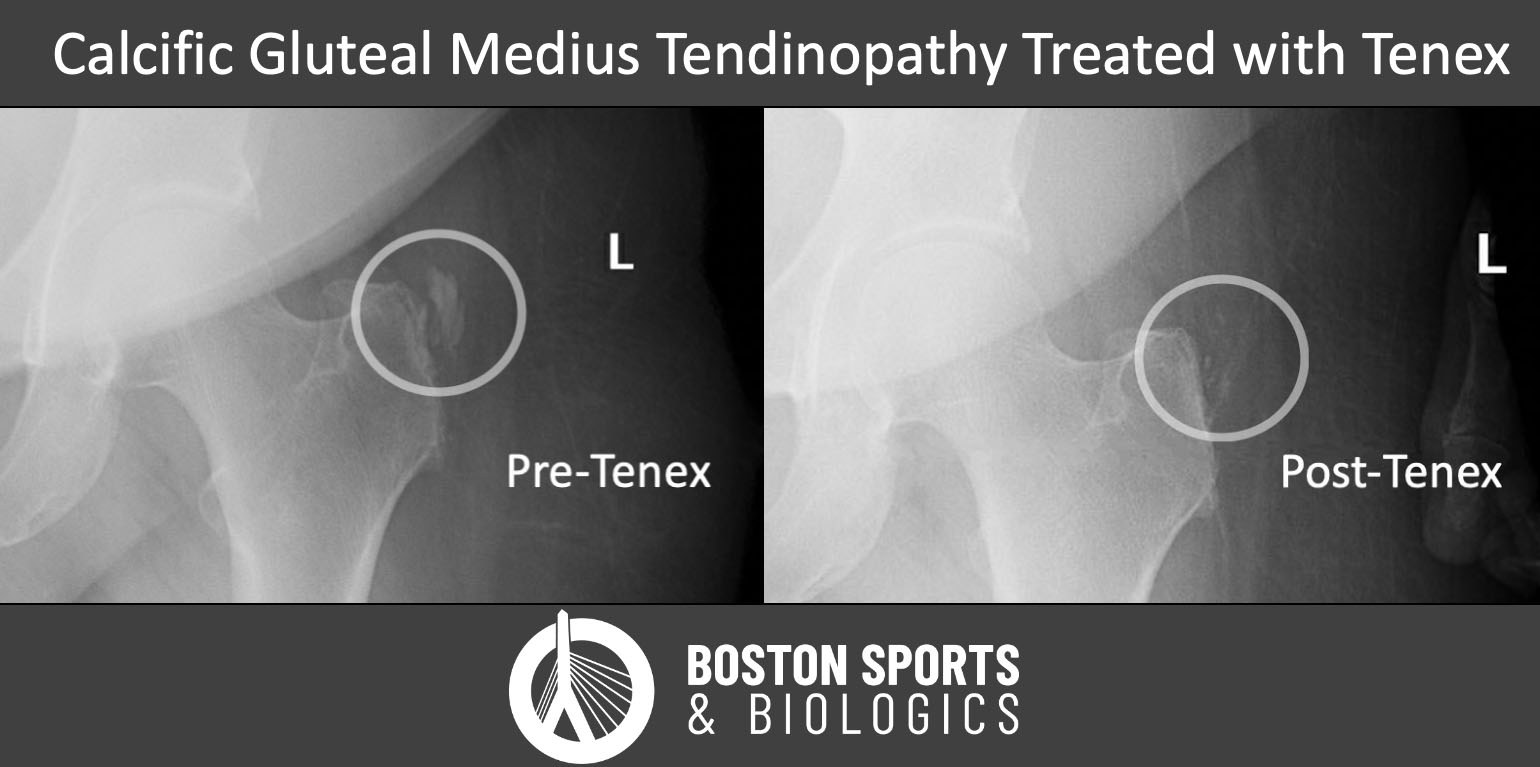

The evidence for Tenex is limited at this time. However, in a small case series by Dr. Champ Baker and Dr. J. Ryan Mahoney, 90% patients who underwent an ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle tenotomy with Tenex were able to avoid an open surgery with the Tenex procedure (Baker et al, 2020). Despite this being a small study, patients were followed for an average of 22 months after the procedure, and only 10% required an open procedure for continued pain.

The rationale behind PRP or Tenex is that these treatments stimulate a healing process by converting a chronic degenerative process into an acute process. In chronic cases of hip tendon pain, the studies have shown tendon degeneration due to repetitive microtrauma. In most cases there was not an acute injury, and the body never responded to the damage created by small repetitive insults to the tendon.

In the case of PRP, the procedure concentrates your own platelets and growth and the PRP is then injected into the damaged tendon introducing inflammatory growth factors and promoting tendon healing (Khan et al, 1999).

The Tenex technique uses high-frequency energy to debride pathologic tissue under continuous irrigation (Kamineni et al, 2015). When the pathologic tissue is removed, it stimulates a healing process by converting a chronic degenerative process into an acute process, also introducing inflammatory growth factors and promoting tendon healing (Khan et al, 1999).

Meniscus tears are one of the most common causes of knee pain in active adults and aging athletes alike. If you’ve been told you have a “degenerative meniscus tear,” you may have also heard that surgery isn’t always the

Read MoreFor patients with chronic adductor longus tendinopathy, a newer option is emerging: ultrasound-guided tenotomy using the Tenex system. Recent clinical evidence suggests this minimally invasive approach may effectively

Read More