Core muscle injuries have been known by various terms over the years, including sports hernia, athletic pubalgia or inguinal disruption. These injuries can represent any number of injuries in the pubic region and affect a number of structures that insert on the pubis or the pubic bone itself (aka osteitis pubis).

These various injuries can present as pain in the lower abdominal area or groin. Although gastrointestinal, gynecologic and urologic sources of pelvic pain have been diagnosed and treated for decades, core muscle lesions have been poorly understood until recent years. In core muscle injuries, despite the historical term ‘sports hernia’ being used there is no true hernia.

The ambiguity in terminology, lack of consensus on the work-up or treatment options, and overlap of symptoms between core muscle injuries and other disorders has led to significant clinical challenges.

Core muscle injury or athletic pubalgia?

Core muscle injury has replaced previously popular terms including “athletic pubalgia” and “rectus abdominis or adductor aponeurosis injury.” Historical terms including “sports hernia” or “sportsman’s hernia” are considered inappropriately, because by definition in core muscle injuries there is no evidence of a true hernia.

Groin pain is common in athletes at all levels, and identifying the causes of chronic groin pain can be clinically challenging.

Understanding the anatomy and biomechanics of the core region is the keystone to accurately diagnosing and treating activity-related pelvic pain. There is a significant overlap of core muscle injuries and symptoms associated with disorders of the proximal thigh, hip joint and abdominal muscles.

The bony structures of the pelvis, and adjacent tendons, muscles and ligaments in the lower chest and upper thigh can all cause pain.

If any of these structures are injured, the biomechanics of the pelvis can change and result in further injury of different core structures. Core muscle injuries are also associated with hip joint pathology, suggesting that altered hip mechanics may also alter the mechanics on the pubic symphysis and adjacent muscles and tendons.

Identifying the causes of chronic groin pain is clinically challenging, but are more commonly associated with athletes who repeatedly engage their core and proximal thigh musculature during competition. Athletes who undergo repetitive kicking, sprinting, or cutting activities in sports such as soccer, football, hockey, and rugby are especially prone to core muscle injuries [Jakoi et al, 2013].

In soccer players, core muscle injuries are estimated to account for 10% to 13% of all injuries per year [Litwin et al, 2011]. One study reported that core muscle injuries were diagnosed in almost half of the 189 athletes with chronic groin pain [Gilmore et al, 1998], and another study identified core muscle injuries as the underlying pathology in 39% of patients [Kluin et al, 2004].

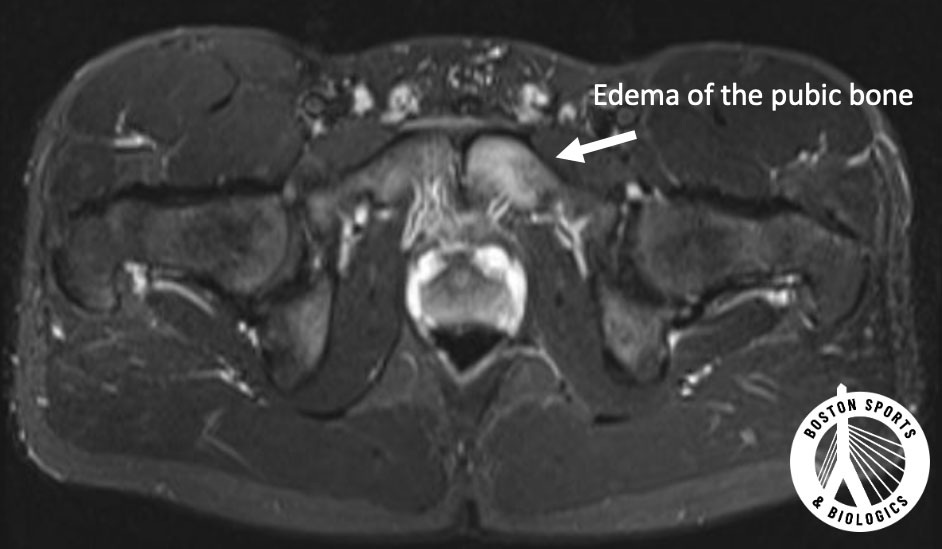

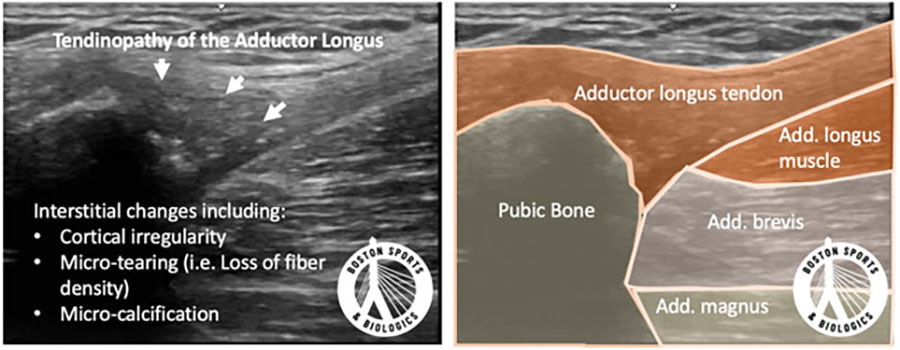

No single imaging modality can be considered optimal for diagnosing and delineating all sources of pelvic pain, particularly in active patients. A core muscle injury is a clinical diagnosis, and the clinical scenario should be considered before any imaging is ordered. Ultrasound can help visualize the adductor and abdominal muscles, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help assess the bone of the pelvis for any stress reactions or bony swelling (edema). If an MRI is ordered, an athletic pubalgia MR imaging protocol is the study of choice for identifying core muscle injuries.

Nonoperative treatment is the initial treatment for core muscle injuries. Formal strengthening programs to increase trunk and lower extremity strength, core stability and address weakness or restriction in the hip, low back and sacroiliac joint can be successful in some patients. In some cases, steroid injections into the pubic symphysis or adductor tendons can be coupled with therapy.

Surgical management is considered if conservative care fails. A varied of surgical procedures have been described, and is often either an open anterior approach or a posterior laparoscopic approach with variations in methods within each category. Procedures can include rectus abdominis repair, adductor lengthening, and hip arthroscopy for the treatment of hip (femoroacetabular) impingement.

The surgical method you are offered as a patient often is determined by the surgeon’s experience and expertise. Although by definition, a core muscle injury is not a true abdominal hernia, some patients are still offered abdominal wall repair with or without mesh to “strengthen” the abdominal wall.

No study directly compares these various surgical approaches, and surgical results vary widely. Surgery has favorable outcomes reported in as few as 63% in some studies and up to 97% of cases in other studies. [Caudill et al, 2008; Sheen et al, 2014].

In a recent proposed algorithm for the treatment of core muscle injuries PRP has been listed as a viable non-operative treatment before considering surgery [Kraeutler et al, 2021]. The scientific literature regarding the regenerative injections is currently limited to case reports. Most common core injuries are centered at the fibroaponeurotic plate and conjoined tendon, and involves the rectus abdominis and adductor longus.

Case have included the successful treatment of a core muscle injury involving the distal rectus abdominus tendon in a lacrosse player [Scholten et al, 2015] and in a profession hockey player [St-Onge et al, 2015]. In both cases, the athlete returned to his prior level of performance within weeks. We have also published a cases of PRP for osteitis pubis and a core muscle injury in a high level soccer player and a rapid return to sport [Park et al, 2022].

Historically, osteoarthritis was described as “wear and tear” of cartilage. We now understand it as a whole-joint disease, involving cartilage breakdown, subchondral bone remodeling, and bone marrow lesions. In recent

Read More