The meniscus is essential to a health knee joint, and acts as a shock absorber and helps stabilize the joint. An injury to the meniscus can impact the joint and increase load on the cartilage predisposing patients to developing osteoarthritis.

Knee meniscal injuries are common and symptomatic meniscal tears are often treated with activity modification, bracing, physical therapy and injections. In cases that do not respond to therapy, surgical repair or debridement is often the next step.

Different meniscal repair techniques have also been described and typically fall into 2 categories: repair of the meniscus or meniscectomy.

Most repair techniques involve suturing the meniscus. In these surgeries, the majority of cases the meniscus is fix or sutured to the joint capsule. This changes the normal anatomy and biomechanics of the joints, and limits the activity of the meniscus during motion (Wang et al. 2019).

Are there any limitations to “repairing” the meniscus?

Other complications include failure of these repairs or retearing of the meniscus. In a systematic review and meta-analysis found 23% of meniscal repairs fail (Nepple et al, 2012), and patients with degenerative tears may not even be candidates for this approach.

Partial meniscectomy still remains the main treatment option in meniscus surgery, however, surgery for degenerative meniscus tears remains controversial. Several randomized controlled studies demonstrated no benefit of partial menisectomy over a pretend or “sham” surgery (Sihvonen et al, 2013).

In the majority of recent randomized controlled studies meniscus surgery was no better than nonoperative treatment (Beaufils et al, 2017). Despite this treatment options for degenerative meniscus tears are limited and these continue to be treated surgically. In fact, half of all of meniscus surgeries are performed on patients older than 45 years with degenerative meniscal lesions (Englund et al, 2008).

Are there any limitations to “repairing” the meniscus?

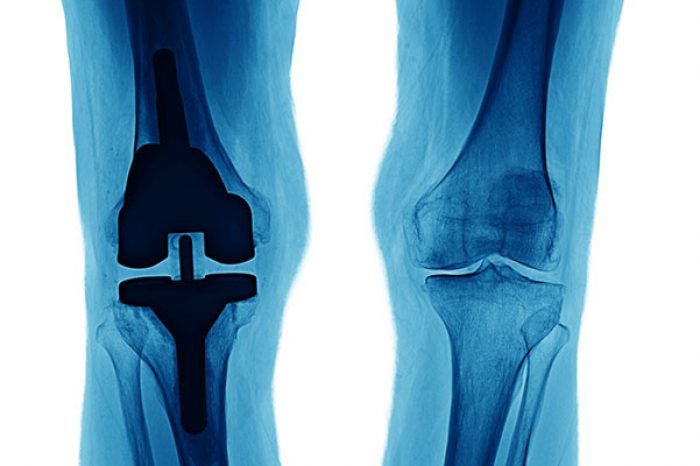

These surgeries are not without complications and may predispose the joint to early-onset arthritis (Longo et al. 2019). A partial menisectomy increases the risk of osteoarthritis at least ten to twentyfold (Vangsness et al. 2014). Other study that followed patients for 5 years after surgery, showed that patients were 2.5 times more likely to get a knee replacement than patient who did physical therapy (Katz et al 2019).

Orthobiologic injections, including platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections, bone marrow aspirate concentrates and mesenchymal stem cells or stromal cells (MSCs) have been proposed to improve pain and promote meniscal regeneration. The intraoperative use of biologic injections for meniscal tears is well established (Massey et al. 2019), but the use of biologics agents in nonsurgical meniscal treatments is limited.

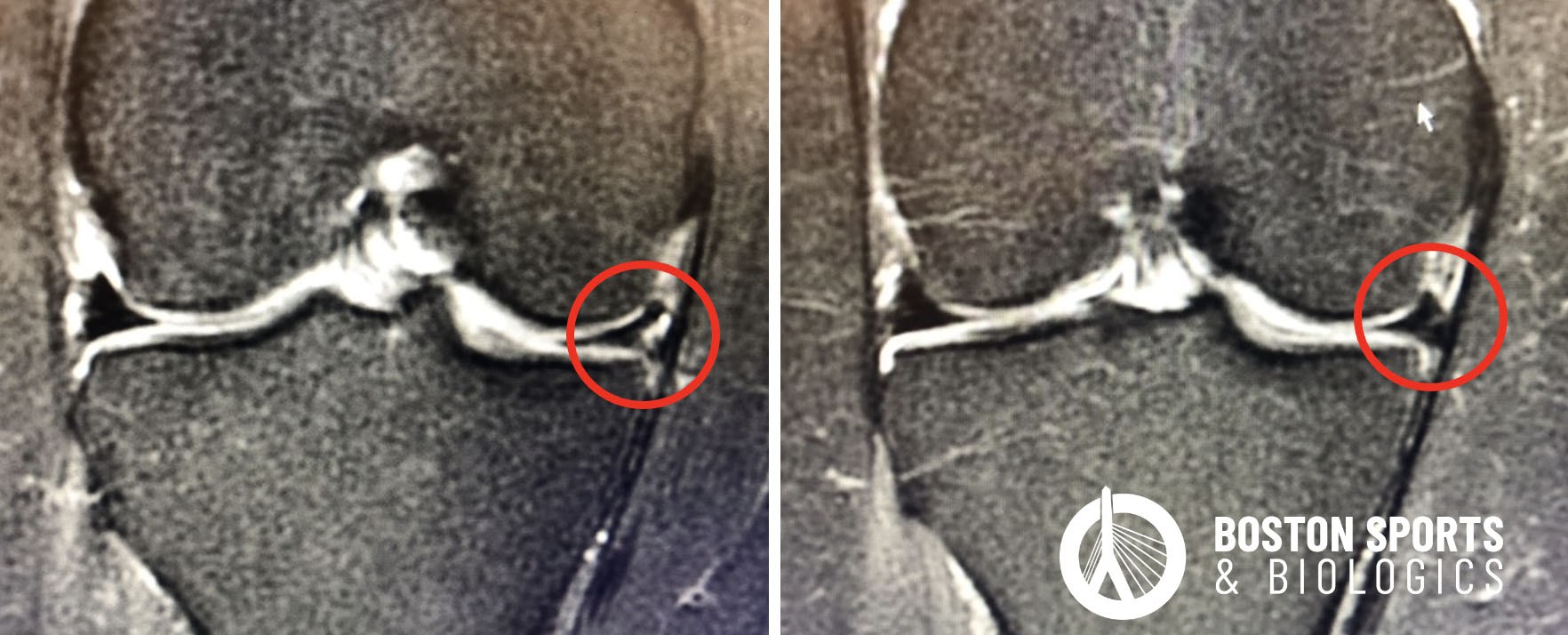

Autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections release multiple growth factors, cytokines and other signaling proteins that play an important role in healing. One double-blind RCT, compared PRP and trephination to trephination alone (puncturing the meniscus to stimulate bleeding and a healing response). In this study, the PRP group showed partial or full healing of the meniscus on MRI in 60% of patients. The authors concluded that the “[trephination] technique with PRP results in a significant improvement in the rate of meniscal” (Kaminski et al. 2019).

Micro-fragmented adipose tissue (MFAT) injections have been studied in a case report (Straino et al, 2017) and a larger case series pilot study using the Lipogems system (Malanga et al. 2021). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) harvested from adipose tissue act as trophic mediators to stimulate differentiation of tissue intrinsic stem cells or reparative cells. MFAT has shown encouraging results and the Malanga et al study was previously reviewed by Journal Watch.

In an animal model using rabbits, bone marrow concentrate mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were able to enhance tissue regeneration (Zellner et al, 2013; Koch et al, 2019).

Adult mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow aspirates were also tested in patients who previously underwent a partial menisectomy in a randomized, double blind, controlled study. The results showed that bone marrow derived stem cells were safe and a there was evidence of meniscus regeneration and improved pain after the injection of mesenchymal stem cells (Vangness et al. 2014).

Not all meniscus tears cause pain and dysfunction, but in cases where a meniscus tear is causing you pain we can precisely target the damaged or torn area of the meniscus using ultrasound. A partial meniscectomy that would remove part of the meniscus has been found to be no better than physical therapy or a sham surgery for degenerative meniscus. To learn more about nonoperative procedures for meniscus tear and a consultation to see if you are a candidate contact us at:

Is stem cell therapy better than cortisone for knee arthritis? Learn the differences, risks, benefits, and long-term results of cortisone vs stem cell knee injections.

Read More